The starting point in the creation of this work was the terrible accident suffered by a young worker friend of ours:

It was one of those warm autumns that struggle to give way to winter. It was Tuesday and I was already thinking about what I would do on Sunday. That Sunday never came and never will. Now stop and tell me: are you happy? No, not in five years, not in ten. Now, now – tell me: are you happy?

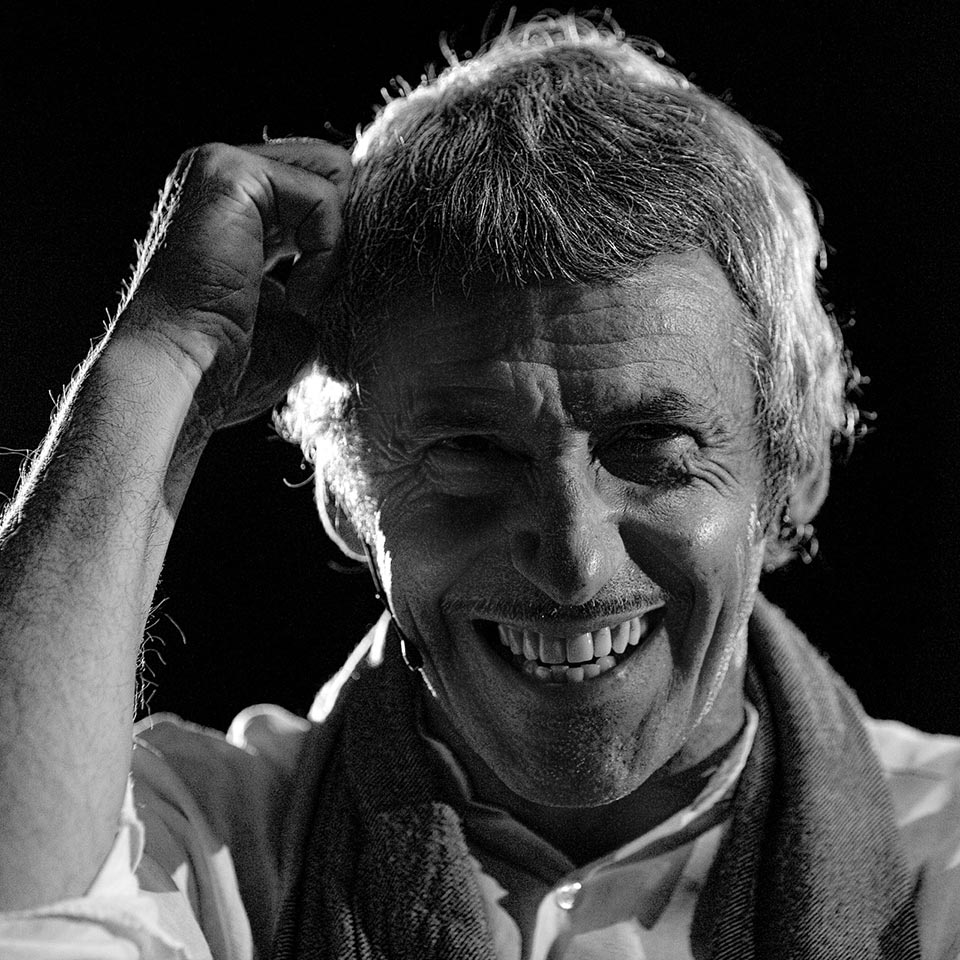

This is where the story of Giammarco M. begins. One evening in November 2006 – at just 37 years old – he was crushed under a 600-kilo gate that broke his back and forever took away his ability to walk.

Giammarco’s story is the story of many (too many) others.

It is the story of someone who had to relearn everything, review everything, rediscover everything.

It is the story of a personal struggle that also wants to become a common struggle, so that people talk about this terrible problem, about these tragedies that strike the world of work every day, like a sort of underground war that no one wants to see or hear about.

How many people die at work each year?

How many people are disabled at work each year?

What type of permanent disability do they suffer?

Which sectors of the job market are most affected?

Is there a real safety problem in the workplace or is it just a matter of “fatality”?

Le statistiche parlano chiaro, rilevato che, solo nel 2008:

874.940 (di cui 143.561 stranieri) – sono il numero degli infortuni sul lavoro

1.120 – le morti bianche

29.704 – le malattie professionali denunciate…

Un altro dato scoraggiante: in Europa, i giovani di età compresa tra i 18 e i 24 anni hanno almeno il 50% di probabilità in più di rimanere vittima di un infortunio sul lavoro rispetto ai lavoratori con più esperienza.

But even more clearly can someone speak who has been pushed into those statistics by force by an invisible hand that is difficult to name: bad luck, destiny or profit?

How does life change, how do affections, friendships, love, sex change?

How and where to find the strength to face this change when the question that haunts you every day is Why, why me? – and there is no other answer than that of the objective working conditions to which thousands of workers are subjected, the blackmail of work that is not there, the nightmare of the crisis, of unemployment, of emigration, of paychecks that never grow, of grueling hours, of security that often is not there because it affects a company’s expenses by 40%. The entire material organization of work should be subjected to scathing criticism. There is no other why. With Stolen Days we tell a personal story to reach and embrace the countless stories that are consumed every day in Italy and around the world.