The story of Kohlhaas is a true story that happened in 16th century Germany, written by Heinrich von Kleist in memorable pages. In my oral storytelling it is as if I had added to the recognizable bony skeleton of Kleist’s story structure, nerves, muscles and skin that no longer come from the original author but from my experience, theatrical and narrative, from my world of visions and poetics. So for example the whole metaphor about the circle of the heart compared to the circle of the horse pen, which comes back several times in the narrative, as a symbolic place of a very human and concrete sense of justice, is my invention, in the etymological sense of the term, something that I found by dint of trying to find my own adherence to Kleist’s story. So little by little the original text was lost and another was born, a work in progress to be tested by ever-changing spectators, year after year, in theatrical and non-theatrical spaces, according to a growth process that to my eyes appears as something organic, as if an increasingly rich and differentiated living organism was forming in my hands.

It happens in the art of oral storytelling that in order to search for inner characters one has to travel long distances, pass through stories of other stories, feel like a stranger in this world after having wandered so much, until one finds that incandescent point capable of generating in turn in the listener a world of visions, not necessarily coinciding with mine. The art lies in not naming too much, in capturing the heart of an experience with a few features, leaving much in the shadows, much still to be accomplished. Kohlhaas is the story of an injustice that, if not resolved through the law, generates a spiral of increasingly uncontrollable violence, but always in the name of an ideal of natural and earthly justice, until the conflict that generates the entire story, what is justice and to what extent in the name of justice one can become a vigilante, is tragically resolved, leaving around the figure of the protagonist an ambiguous aura of a possible hero of his time. The moral questions that the story raises and leaves hanging, seemed to me, when he begins to tackle the memorable undertaking of the story, a way to talk about the 70s, to talk about those conflicts in which my generation found itself, that of ’68, when in the name of a superior ideal of social justice we ended up bloodying squares and cities. Ultimately, if I wanted to look back at my artistic career, without Kohlhaas I would not have come to tell Corpo di Stato, a theatrical story broadcast live on television on the night of May 9, twenty years after Moro’s death, to be able to find the same conflicts, managing this time to talk about them from the inside, as a subject involved in the narrated facts. An ancient theme, therefore, tragic in tradition and form, which continues to capture me, because the narrator cannot help but narrate what epically involves him in his entire person, and this is what happens to me: I could not tell just anything.

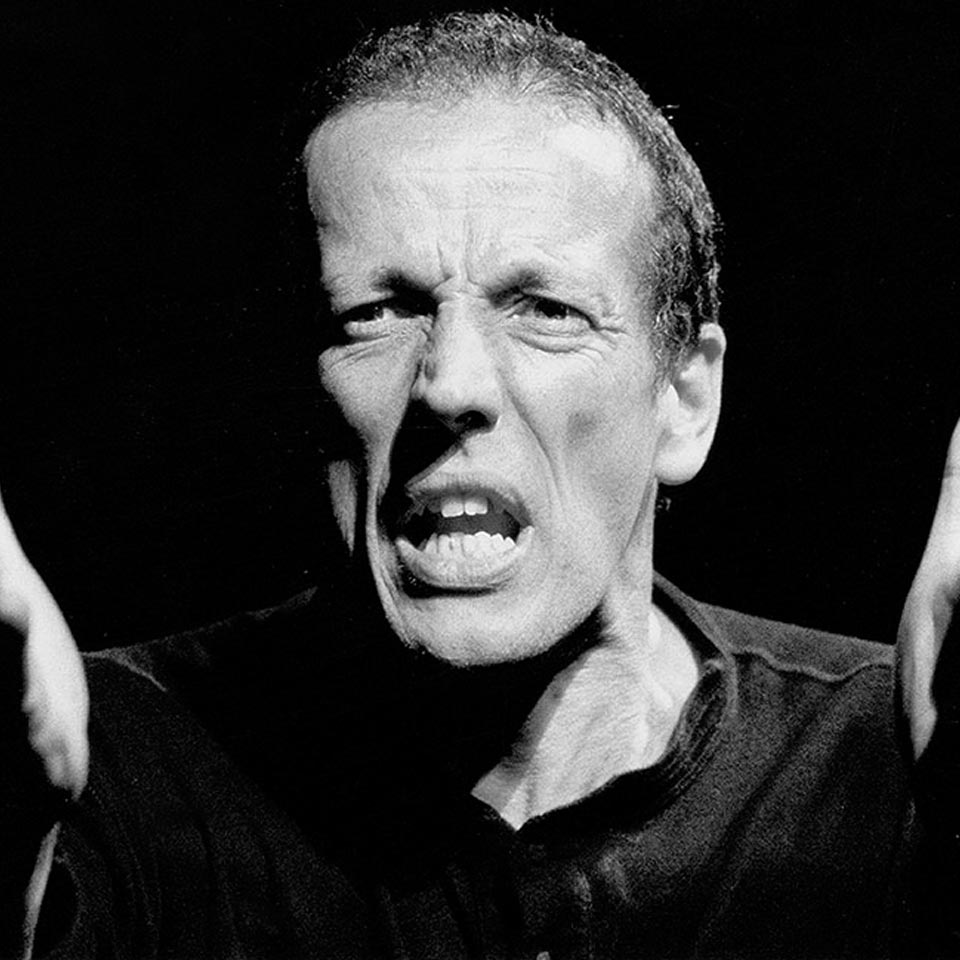

Marco Baliani